Introduction

Thorough analysis of Ireland’s experience of the First World War necessarily begins in 1912 and ends in 1923. Unlike any other part of the United Kingdom, Ireland’s war experience was inseparably linked to debates over its place in the UK which affected how people engaged with the war effort throughout 1914-1918, with 1916 a pivotal year. Even after independence, the memory of the war continued to be profoundly connected to politics. Such memory remains politically salient while connected to wider events, with 2012 to 2022 or 2023 widely termed a “Decade of Commemorations” or “Decade of Centenaries”.[1] After a brief summary of previous research, this article thus considers politics in Ireland in 1912, before examining Irish military involvement in the war and the effect that had on society, politics and the economy. It concludes with reflections on memory of the period.

Research on the field is in a state of growth, and has been for almost three decades since historians and the public began to reassess existing work. Thorough reflections on writing until the early part of that growth are provided by Keith Jeffery in Ireland and the Great War (2000).[2] Much work has appeared since then, however, and needs to be added to the titles cited by Jeffery. An online bibliography[3] fulfils part of that task and relevant points from specific works are cited below. However, to summarise phases and themes in existing work, seven points can be made. First, issues relating to recruitment have been persistent, with writers addressing why and in what numbers Irish people were involved in the war effort, including discussion of overall casualties.[4] Second, local studies have been central, whether linking the war and politics,[5] or telling the story of an area, both in terms of the home front and also the experiences of those who served.[6] Third, Ireland’s war is now well served by unit histories, whether dealing with the three volunteer divisions across the war,[7] or more specific battalion studies.[8] Fourth, the war has been addressed thematically.[9] Fifth, there are a vast number of general studies of Ireland’s revolution,[10] which should be read alongside war studies, and have included rediscovery of parliamentary Irish nationalism.[11] Sixth, a significant growth area is the study of remembrance and/or commemoration.[12] Finally, general surveys of the war as a whole, or aspects of it across a broad period, serve as standard reference points.[13]

Home Rule and Irish Politics before the First World War

If Ireland’s Decade of Centenaries begins with commemoration of 1912, the story of 1912 goes back to the Act of Union (1800), which scrapped Ireland’s Parliament and saw the country become part of a formal union in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, Irish nationalists campaigned for, among many other issues, repeal of the Union.

However, by the 1870s, “Home Rule” had become the clarion call of nationalists. As initially proposed, this would have involved an Irish Parliament controlling domestic matters, but as part of a federal UK, with Irish MPs taking seats in an Imperial Parliament in Westminster, which would control defence, foreign policy, some fiscal policy, and macroeconomic matters.[14] Home Rule steadily secured mass support in Ireland. Home Rulers, by then known as the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), won eight-five of Ireland’s 103 seats in the 1885 general election.[15] Meanwhile, the Liberal Party under William Ewart Gladstone (1809-1898) became persuaded of the case and, short of a majority in Parliament after the 1885 election, introduced a Home Rule Bill for Ireland. However, Conservatives were resolutely opposed, as were some Liberals. The Liberal Party split and Home Rule was defeated. For the next two decades, Home Rule was a persistent and occasionally dominant issue within British politics. That was so much the case that Conservatives and Liberal Unionists (those Liberals who opposed Home Rule) worked together under the shared label of “Unionist”. A Liberal government again proposed Home Rule in 1893, but the Unionists controlled the House of Lords and could block any legislation. Nothing could bring about Home Rule unless the Liberals came to dominate the Lords, or the powers of the Lords were changed. It was the latter that happened in the 1911 Parliament Act, brought about by a dispute over David Lloyd George’s (1863-1945) “People’s Budget” of 1909-1910. Following deadlock between Lords and Commons, the Act removed the Lords’ permanent blocking powers.

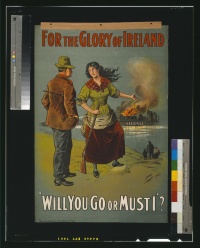

When a Third Home Rule Bill was introduced in April 1912 it became clear that it would eventually be passed, raising the prospect of conflict in Ireland. Although the vast bulk of Irish people had supported Home Rule, the Protestant minority, which constituted the majority of people in much of the north-east of Ireland, commonly referred to as Ulster, were vehemently opposed. They feared that Home Rule would mean “Rome Rule”, with a Dublin Parliament dominated by the Catholic majority. A militant campaign of resistance ensued. On 28 September 1912, under the leadership of Edward Carson (1854-1935), nearly half a million men and women pledged their opposition to Home Rule through signing the Ulster Covenant, including resistance “by all means necessary”, raising the spectre of violence.[16] When the Third Home Rule Bill passed the Commons on 16 January 1913, the prospect of violence, even civil war, soon became real. Unionists established the Ulster Volunteer Force,[17] a paramilitary group which, within a year, claimed to have over 90,000 members. Then, in November 1913, nationalists responded by forming the Irish Volunteers (IVs) who were ready to fight in defence of Home Rule. Initially, the IPP, led by John Redmond (1856-1918), was wary of the IVs, but they steadily gained control of the organisation and endorsed it, with its membership reaching 129,000 by May 1914. 1913 also saw the formation of a small, Dublin-based socialist militia, known as the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), which was likely to side with nationalists in the event of armed conflict. While these rival armies had been formed, the Lords had rejected Home Rule; however, they could now only reject each bill twice, and the Commons finally passed it in May 1914. Faced with the prospect of war in Ireland, the Liberal Prime Minister, Herbert Henry Asquith (1852-1928), sought a compromise whereby Ulster could be excluded from Home Rule. Efforts to do this, or seek another solution, were ongoing as war broke out on 4 August 1914.

Politics at the Outbreak of the War

Faced with other priorities, Asquith ceased trying to amend Home Rule. Instead, the Home Rule Bill received Royal Assent on 18 September 1914 but implementation was suspended on the same day for a year. That suspension was later extended periodically throughout the war.[18]

Tensions ran extremely high in Ireland in the ten days or so that preceded the British declaration of war. In particular, the shooting of three civilians (with scores more wounded and one further death two months later from wounds sustained in the incident) by British soldiers in Bachelor’s Walk in Dublin on 26 July saw a mass public turnout at the funerals of the three who died that day. The dead had been shot following the landing of guns at Howth by nationalists, but there was no evidence that they were gun-runners, and a Royal Commission later placed blame on local police.[19] By the eve of war, however, circumstances had changed to a marked degree, to the extent that the British foreign secretary, Edward Grey (1862-1933) could declare on 3 August “The one bright spot in the whole of this terrible situation is Ireland.”[20] This was partly because it had become clear that nationalists would support the British war effort, with John Redmond declaring that if British troops were withdrawn from Ireland to fight on the continent, the Irish Volunteers would be used for the defence of its shores (including alongside the UVF). Carson had also pledged Unionist support. There was nothing remarkable in that – how could Unionists not heed a call to fight for King and Country? However, Carson was also in the process of agreeing with the War Office that the Ulster Volunteer Force would become the basis of a new division in the British army, maintaining much of its own command, with the men from individual UVF units going together into one infantry battalion. Once Carson was satisfied that Home Rule would not be implemented for the time being, he was able to commit his party to this 36th (Ulster) Division which began to be formed in early September.[21]

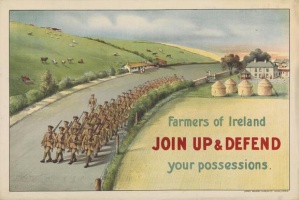

Meanwhile, six weeks into the war, after stories of German atrocities in Belgium had affected public opinion, John Redmond gave greater support for the war effort. In a speech at Woodenbridge, County Wicklow, on 20 September, which is remembered as marking a shift in Redmond’s position, he called on all Irishmen to enlist in the British military. This in fact followed a lower profile statement in Parliament on 15 September (the day on which Asquith pledged to place Home Rule on the statute book) that on his return to Ireland he would say to all of his “fellow countrymen...that it is their duty, and should be their honour, to take their place in the firing line in this contest”. That statement was itself followed two days later, on 17 September, by a call for all Irish recruits to be part of an “Irish Brigade” within the British Expeditionary Force. [22] While this new position was not universally popular among nationalists, the vast majority supported the line. Redmond’s supporters were ousted from the Irish Volunteers’ Provisional Committee, but among the membership around 80 percent backed him, forming a new organisation, the Irish National Volunteers (INVs).

Following Woodenbridge, Redmond sought to establish an “Irish Corps” within the British army, sometimes deploying the term “Irish Brigade”, which was reminiscent of Irish service in previous “foreign” armies. By mid-October, it became clear that this Brigade would be in the already established 16th (Irish) Division and Lord Kitchener (1850-1916) soon agreed to clear one brigade (47th Brigade) of that division to take men from the INVs.[23] With something approaching a nationalist unit now in place in the British army, Redmond set about recruiting.

That the war so soon saw two rival private armies both under the British flag as volunteers depended on four key factors. First, both sides had ensured that their cause was not defeated through the passage or defeat of Home Rule. Second, through Home Rule being suspended temporarily, both believed that they could in due course secure a satisfactory solution if they supported the British Empire in its time of danger. Third, the two political volunteer divisions had enough of an air of uniqueness about them to ensure that they did not look like just any other British army division. Finally, each side was fighting for causes entirely consistent with their politics: “King and Country” for unionists, and for nationalists both “the rights of small nations” and “Catholic Belgium”. Ireland thus entered the war more united than it would ever be in the future. At this stage, opposition to the war was marginal while there was broad support for what was seen as a “just” war.[24]

Ireland’s Military War

The Regular Army

At the outbreak of war, Irishmen were already serving throughout the British military, with just over 20,000 in the army.[25] In the Royal Navy and embryonic Royal Flying Corps they were not concentrated in specific ships or units. In the army, men served in many non-Irish regiments. Indeed, the first Victoria Cross of the war was awarded to an Irishman serving in the 4th Royal Fusiliers, Lieutenant Maurice James Dease (1889-1914). [26] Yet inevitably, Irish men’s army service was focused on the Irish regiments. These were comprised of the Irish Guards (1st Battalion, based at Caterham in Surrey) and eight line regiments (their main depots in Ireland, often indicating their core recruiting area, are in brackets):[27]

- Royal Irish Regiment (Clonmel)

- Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers (Omagh)

- Royal Irish Rifles (Belfast)

- Royal Irish Fusiliers (Armagh)

- Connaught Rangers (Galway)

- Leinster Regiment (Birr)

- Royal Munster Fusiliers (Tralee)

- Royal Dublin Fusiliers (Naas)

Each regiment was comprised of two battalions, the 1st and 2nd, each with a peacetime strength of approximately 500 to be supplemented in war by a similar number of reservists. Meanwhile, each regiment had 3rd and 4th reserve battalions (and in the case of the Leinsters, Dublins, Munsters and Royal Irish Rifles, a 5th) as training units for reservists.[28]

There were four Irish cavalry regiments, not all based in Ireland:

- 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards (Newport, Monmouth)

- 5th Royal Irish Lancers (Woolwich)

- 6th Inniskilling Dragoons (Newport, Monmouth)

- 8th Kings Royal Irish Hussars (Dublin)

These were supplemented by two reserve cavalry regiments, the North Irish Horse (Belfast) and the South Irish Horse (Dublin).

In line with standard procedures of the British army, when war broke out one regular battalion of each infantry regiment was based at “home” (which often meant England rather than Ireland) and one overseas. Five Irish battalions were in India (the 1st Irish Regiment, Inniskillings, Connaughts, Leinsters and Dublins), as were two cavalry units (6th Inniskilling Dragoons and 8th Royal Irish Hussars), two in Aden (1st Irish Rifles and 2nd Irish Fusiliers), and one in Burma (1st Munsters). Thus when the original British Expeditionary Force was formed, the home battalions rapidly became part of it in different divisions. The first Irish battalion to arrive in France was the 1st Irish Guards on 13 August, followed by the 2nd Munsters, Connaughts, Irish Regiment and Irish Rifles the next day. By the end of August, all regular Irish infantry and cavalry units (plus the North and South Irish Horse) based at home were in France except for the 2nd Leinsters who arrived on 12 September. As for those units overseas, all regular Irish battalions except the 1st Inniskillings, Dublins and Munsters (all of which would be deployed at Gallipoli in April 1915) had landed in France by the end of 1914. Consequently, Irish regiments took a significant part in the early stages of the war on the Western Front, in particular at Mons and Le Cateau from 23 to 26 August, La Bassée in October and 1st Ypres in October to November.[29]

The continued contribution of the regular battalions went well beyond 1914. Regular Irish battalions played a particularly important role in the early stages of the Gallipoli campaign with the 1st battalions of the Inniskilling, Dublin and Munster Fusiliers landing at Cape Helles on 25 April 1915. Each battalion remained at Gallipoli until the allied evacuation in January 1916, and went on to serve on the Western Front.

Volunteer Divisions

Ireland also contributed three volunteer divisions of the new army, the 16th (Irish) and 36th (Ulster) divisions already discussed, plus the 10th (Irish). The 10th was the first to be established, on 21 August 1914, and consisted of battalions from across Ireland. It had no political allegiance and consequently included both Protestant and Catholics volunteers, some of whom had been involved in the Ulster Volunteer Force or the Irish Volunteers. Of the volunteer divisions, it was the first to be recruited and the first to see action, at Gallipoli.[30] There, on 6 and 7 August 1915 the division took part in the landings at Suvla Bay and Anzac Cove, subsequently fighting at Chocolate Hill, Sair Bair and Hill 60 before withdrawing on 29 September after losing 2,017 men killed in action or who died of wounds.[31]

The 10th Division’s next posting was Salonika, where it took part in the fighting at Kosturino on 7 and 8 December 1915 before serving in Macedonia in 1916-17 and Egypt/Palestine in late 1917 and early 1918 where it helped to defend Jerusalem.[32] Over April to May 1918 all Irish battalions steadily left the 10th Division (replaced mainly by Indian battalions) for redeployment to the Western Front where they saw service scattered across different divisions.

The two other volunteer divisions served only on the Western Front. Efforts were made to form the 36th (Ulster) Division entirely from Ulster (except for the artillery which was formed from London volunteers.)[33] It trained in Ireland until July 1915 when it finished training at Seaford, not going to France until October 1915. Its first major engagement was on 1 July 1916, the first day of the battle of the Somme. The division was initially successful in securing parts of the German lines at the Schwaben Redoubt, but divisions either side of it made less progress. In particular, the 32nd Division failed to take Thiepval village and the 36th came under heavy fire from machine guns there. The 36th lost over 5,000 men as casualties that day, of whom just over 2,000 were killed.

The 16th (Irish) Division also fought on the Somme. Though notionally the nationalist counterpart to the 36th, in reality only one brigade of the 16th Division (47th Brigade) had been solely recruited from the Irish National Volunteers. But the 16th still stands as the most coherent representation of nationalist Ireland on the Western Front. It left Ireland later than the 36th, training in England from September 1915, and did not reach France until December. Its first major action was on 3 September 1916 at Guillemont, and then on 9 September at Ginchy. Both were successful advances in which objectives were gained and held during the phase of the Battle of the Somme during which the British army was making consistent gains. Tom Kettle (1880-1916), a former nationalist MP and scholar, who was then serving as a junior officer in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, was mortally wounded at Ginchy.

Following the Somme, the next major engagement for the 16th and 36th divisions was at Messines on 7 June 1917. This battle holds a special place in the memory of the two divisions because they fought alongside each other (the 16th on the left flank of the 36th), capturing Wytschaete in what was probably the most successful advance by the British army at that stage of the war. Some symbolism of the occasion was found in the death of Major William “Willie” Redmond (1861-1917), nationalist MP for East Clare. Serving with the 6th Royal Irish Regiment in the 16th, the stretcher-bearers who made the first efforts to save his life were from the 36th.[34]

After Messines, the 16th and 36th took part in the early stages of the Third Battle of Ypres, specifically Langemarck and engagements in late March 1918 during the German spring offensive. However, by this stage, both divisions were ceasing to resemble the political divisions which had left Ireland in 1915. There had been reinforcements from Great Britain after the Somme, and there had been reorganisations of the divisions (as there were throughout the British army) from late 1917. Although other Irish battalions joined both divisions, they had no political character, while some battalions from throughout the UK were also transferred in.[35]

Air, Sea and Other Theatres

Although most fighting took place on the Western Front, it did not all occur on land, and some of it was very far from either the well-known fronts in western Europe, Gallipoli, Salonika or Palestine. Men from Ireland took part in operations to support the Russians on the Eastern Front.[36] Men from Belfast saw action in Italy, Mesopotamia, East Africa, South Africa and the Falkland Islands.[37] In the air, Edward “Mick” Mannock (1887-1918) won the Victoria Cross and is often hailed as an Irish war hero, though his connections to Ireland are tenuous.[38] At Jutland, the UK’s great naval battle of the war, Dublin men were lost on ships such as the HMSs Indefatigable, Queen Mary and Defence.[39] There were also civilian deaths when non-military vessels were sunk, most notably the Lusitania, which was sunk off the Cork coast on 7 May 1915.[40]

Service and Recruitment

Across the areas of service, motivations for enlistment have been the subject of significant debate. David Fitzpatrick has made one of the most significant contributions in a seminal article on the “logic of collective sacrifice”.[41] Challenging the idea that economic factors offer the primary explanation for Irish service in the British military, Fitzpatrick argues that “the readiness of individuals to join the colours was largely determined by the attitudes and behaviour of comrades – kinsmen, neighbours, and fellow-members of organizations and fraternities.”[42] This is based on the fact that enlistment tended to be highest where economic insecurity was less.[43]

Meanwhile, there have been other general interpretations of matters such as discipline and the effectiveness of Irish troops.[44] However, the central and ongoing debate on Ireland’s war contribution concerns the levels of service and fatalities. Reviewing the debate, Keith Jeffery points out that the figure of 49,000 dead put forward in Ireland’s Memorial Records includes all those who served in Irish units, regardless of where they were from.[45] So it is commonly accepted that that figure is likely to be too high, and alternatives that have emerged from academic research range from 25,000 to 35,000, with the latter tending to be more commonly cited.[46] These figures, however, do not include the thousands of men of Irish birth who lost their lives while serving in the armies of the British dominions and the U.S. forces. Less contentious is a figure of approximately 210,000 men from Ireland having served in the military during the war.[47]

Society and Economy

Women

Just as volunteering drove Ireland’s men to military service, it also led women to a variety of activities.[48] Probably the majority of those involved were Protestant (reflecting established patterns in Irish charity),[49] but voluntary work did cut across political divides. Organisations including the Ulster Volunteers and the nationalist Cumann na mBan took part in the initial meeting to establish Red Cross work in Dublin on 10 August 1914.[50] Over 4,500 women from Ireland served in nursing and auxiliary roles in Voluntary Aid Detachments and as members of Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Army Nursing Service.[51] A small number of these women died while serving on the Western Front.[52]

Such work involved the standard tasks of the Red Cross around the world, but there was one specifically Irish angle. The Irish War Hospital Supply Depot provided surgical dressings made from the sphagnum moss with which Irish bogs were replete. Women and children were the volunteer workforce.[53] In contrast to the rest of the UK, Irish women did not take on many of the roles which had been the work of men, since there was no conscription in Ireland, although there was work in munitions manufacture.[54] However, women from the College Guild at Alexandra College (Dublin) housed Belgian refugees, knitted socks and served in Western Front canteens.[55] Gifts for soldiers were provided by a range of organisations from local groups throughout Ireland to the Ulster Women’s Unionists Council, which even provided shamrock for the 36th (Ulster) Division on St. Patrick’s Day in 1915.[56]

Economy and Munitions

Of course, many women were already working in industries which responded to and benefited from the war. Inevitably, that applied to Belfast, where most heavy industry was located. Shipbuilding and aircraft manufacture flourished. Linen initially lost continental orders but recovered as a supplier of aeroplane cloth. Mackie’s (an engineering firm) in Belfast turned to munitions and ultimately produced 75 million shells. Kynoch’s in Arklow was already in existence producing high explosives and employing over 2,000 workers. New National Shell Factories were opened in Dublin, Waterford, Cork and Fermoy, but employed only just over 2,000 between them (700 men, 1,400 women). Irish trades unions began the war talking less supportively of the national effort than their counterparts in Britain, but the conflict’s demands saw them closely incorporated into the economic system by the armistice.

Farming prospered, with wages rising and the value of agricultural produce doubling over 1913-1918. There was an increase in tillage which contributed to Ireland having a surplus rather than a shortage of food during the war. Ireland greatly improved its trading position, increasing its excess of exports of imports from £3.2m in 1914 to £17.3m in 1919. Levels of poverty and unemployment fell.[57]

Irish Politics during the War

At the outbreak of war, the IPP retained its dominance of Irish politics. With Home Rule on the statute book there were reasons to believe that support of the British war effort could deliver the IPP’s long sought after goal. However, implementation of Home Rule became steadily more distant, not least after Carson became a minister in the coalition government formed in May 1915 while Redmond was excluded.[58] A sign of rumbling discontent was that the Catholic Church in Ireland steadily became less supportive of Redmond’s line, ceasing to support recruiting by the end of 1915.[59]

At Easter 1916 “All changed, changed utterly”, in the words of W.B. Yeats (1865-1939). [60] Prior to 1916, radical (or “advanced”) nationalists or republicans had been few in number. Arthur Griffith (1872-1922) formed a separatist party, Sinn Féin, in 1907, but it was a marginal force by the beginning of the war. Dissenters from the Redmond line existed in a small minority of Irish Volunteers led by Eoin MacNeill (1867-1945), and more significantly, two more militant groupings: first and foremost the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and the smaller ICA.[61] It was within the Military Council of the IRB, that an armed rising was planned from August 1914, with Thomas “Tom” Clarke (1857-1916) usually seen as the most significant figure. Plans for a Rising in Dublin were based on the view that if arms could be secured from Germany, if the German navy could prevent the landing of British reinforcements, and if there could be simultaneous uprisings in other parts of Ireland, it would be possible for the rebels to take power in an Irish revolution.

On Easter Monday, 24 April 1916, the rebels proclaimed a Republic from the portico of the General Post Office in Dublin.[62] Read by Patrick Pearse (1879-1916), who had been named as President of the Provisional Government, their Proclamation claimed “the Irish Republic as a Sovereign Independent State”.[63] Treason against the British state was confirmed in the assertion of support from “gallant allies in Europe”, which meant the Central Powers. As many as 1,600 ultimately took part - including women such as Constance Markiewicz (1868-1927) - in seizing key buildings around Dublin, but support from elsewhere was not forthcoming. German arms were intercepted off the south-west coast and naval support did not materialise. Action outside Dublin was restricted largely by MacNeill who, believing the insurrection to be doomed, countermanded the order for the mobilization of the Irish Volunteers. The British reacted by sending reserve troops, many of them from Irish regiments, to quell the rebellion. Fierce fighting saw significant damage to central Dublin. On 29 April, the rebels surrendered. Sixty-four of them had been killed, with 132 British soldiers and around 230 civilians.[64] The proclamation had also referred to the “readiness” of Ireland’s “children to sacrifice themselves” which has led to some debate over how far the Rising was intended to be an heroic sacrifice to inspire the nation. However, such a belief in “blood sacrifice” was probably only held by Pearse and perhaps a few others and, in terms of rhetoric, was by no means unique to Irish Republicanism during this period.[65]

Initial reactions to the Rising were far from positive. There were vivid stories of women whose husbands were away fighting in the British army treating arrested rebels with hostility.[66] But what changed opinion “utterly” was the brutal British treatment of rebel leaders, with fifteen of them executed between 4 and 12 May 1916, combined, in the longer term, with an increase in popular anti-war and therefore anti-British sentiment.[67] Opinion did not, however, turn immediately. There was a new phase of negotiation between the Redmondites and the British, with Home Rule offered immediately in July 1916, but that failed because nationalists objected to permanent exclusion of Ulster (as did southern Unionists).[68] Following this, Sinn Féin became a vehicle for Irish discontent in a series of by-election successes. During the war there were nineteen by-elections in seats held by members of the IPP. Prior to the executions only one of the eight seats was lost (and that to an Independent Nationalist). However, after the executions, while the first was held, Sinn Féin won four of the next five contests, and six of the eleven in total.[69]

Opinion was clearly shifting by May 1917 when Sinn Féin had already gained Roscommon North and Longford South. The British government announced an Irish Convention of all parties to discuss options, which ran until the spring of 1918. However, it failed to reach agreement, partly on the issue of Ulster’s exclusion. In any case, Sinn Féin boycotted the Convention. Meanwhile, on 6 March 1918 John Redmond died and was succeeded by the more hard-line John Dillon (1851-1927). [70] In response to the German spring offensive of March 1918, conscription was introduced for Ireland to tackle a manpower shortage (recruitment had fallen markedly in Ireland in the absence of conscription.)[71] The IPP joined Sinn Féin and the Catholic Church in an anti-conscription pledge on 21 April 1918 and a general strike two days later. This radicalisation of the IPP helped to defeat Irish conscription, which was dropped in June, but came too late to save most IPP seats at the December 1918 general election. Sinn Féin rose from its six by-election gains to a total of seventy-three. The IPP was virtually annihilated gaining just six compared to its eighty-three Irish seats eight years before. Devolution was no longer enough for an Irish population worn down by war, dismayed by delays to Home Rule, appalled by the executions of rebel leaders, and affronted by an attempted introduction of conscription. The struggle was now one for independence.

Aftermath

The end of the war did not see war’s end in Ireland. Most soldiers did not return home until after the 1918 election had seen Sinn Féin almost destroy the IPP. For those who in 1914-1915 had believed that enlisting would secure Home Rule, return exposed them not only to the fact that it had not, but also that most nationalists now wanted more radical change. Meanwhile, in the north, unionism was commemorating the service of the 36th (Ulster) Division as a sign of its loyalty to the empire.

Following the Easter Rising and the execution of its leaders, Éamon de Valera (1882-1975) [72] had emerged as the leader of Sinn Féin while the Irish Republican Army (IRA)[73] had been formed from a reorganisation of the Irish Volunteers. The IRA, which would not become known as such until 1919, included some former members of the British army whose experience was much valued, perhaps most notably Tom Barry (1897-1980) and Emmet Dalton (1898-1978).[74] It began a war against the British in January 1919, variously known as the Anglo-Irish War, the War of Independence or the “Black and Tan” War (after the nickname for the first units of British auxiliary forces, which began arriving in Ireland in March 1920).

Sinn Féin was meanwhile using its political power, not in Westminster (Sinn Féin did not recognise London’s authority and pursued a policy of abstention), but instead by running a shadow government in Ireland. This was done through Dáil Éireann, an Irish parliament, consisting of those elected as Sinn Féin MPs at the 1918 election. All other Irish MPs were invited but did not take part in this revolutionary government which was declared illegal by the British on 11 September 1919.[75]

Meanwhile, the British government was trying to develop an alternative solution, passing the Government of Ireland Act in December 1920, which created two “Home Rule” parliaments in Belfast (for counties Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone, creating Northern Ireland) and Dublin (for the other twenty-six counties). The ensuing elections of May 1921 saw a parliament elected and established in Northern Ireland. However, of the 128 MPs elected in the south, only the four unionists elected for Dublin University took up their seats. All the other 124 were unopposed Sinn Féin candidates who instead formed a Second Dáil.[76] The war with the British continued until 11 July 1921 when a truce was agreed. According to the most recent and reliable research, over 2,100 were killed during the years of the War of Independence. Just under 900 (or 48 percent) of those who lost their lives were civilians, while just over 1,240 (or 52 percent) were combatants. Of the latter, some 467 were serving in the IRA when they were killed while a further 776 were members of the Crown Forces (comprising Irish police, British paramilitary auxiliaries and units of the regular British army).[77] Negotiations between the British and republican leaders from the Second Dáil resulted in the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 6 December 1921. This created the Irish Free State, which remained within the British Empire as a self-governing dominion, similar to former colonies such as Australia. The leading figure of the IRA, Michael Collins (1890-1922), [78] led negotiations for the Irish. Collins was weary of war and believed that compromises could be a first step towards full independence. He also understood the enormous significance of a British military withdrawal from most of the island. But two concessions proved especially unacceptable to the Dáil’s President Éamon de Valera, even though the Dáil had narrowly endorsed the Treaty: the British King remaining as Head of State, which meant that members of the independent parliament would still have to swear allegiance to George V, King of Great Britain (1865-1936), and Northern Ireland being allowed to opt out of the new state. As a result, in a place which had become accustomed to using armed struggle as a political weapon, civil war ensued. After tensions between pro and anti-treaty elements of the IRA throughout early 1922, the battle of Dublin from 28 June saw the shelling of the Four Courts and street fighting over the course of a week.[79] The war continued in many parts of Ireland until a ceasefire on 30 April 1923 and the surrender of weapons by the hugely outnumbered and eventually defeated anti-treaty forces a month later. Estimates for how many had been killed run to as many as 5,000, though there are no definitive figures.[80]

Conclusion

An overall assessment of the unique nature of Ireland’s First World War is best rooted in the experiences of veterans and in memory of the war. For those returning, the changes in Irish politics and the emergence of the British army as the enemy meant that for nationalists, service in the British army was unlikely to be celebrated. However, responses were rather more mixed than might have been expected in the south, with historians pointing to varying features of memory, including disengagement, amnesia, embarrassment and resentment.[81] Though some work[82] has pointed to active hostility towards veterans in the south, a recent and more detailed study has suggested that by and large veterans were well-treated there.[83] Meanwhile, the Irish Nationalist Veterans Association was active across Ireland in the 1920s for those who had heeded Redmond’s call, though much nationalist memory, especially in Northern Ireland, steadily became private rather than public. Republicans wanted no part in what became pro-British unionist commemorative activities heavily linked to bolstering the new Northern Ireland state.[84] The major shift towards nationalist Ireland’s amnesia regarding the First World War began in the decades after 1945, with the fiftieth anniversaries of both the Easter Rising and the Battle of the Somme in 1966 dividing commemoration along regional and religious lines. This divided memory was greatly exacerbated by the profound cultural entrenchment that emerged after the outbreak of the Northern Ireland conflict, commonly referred to as the “Troubles”, in 1969.

However, significant changes have taken place, especially since the paramilitary ceasefires of 1994, which began the end of the “Troubles”, though there were signs of a shift as far back as 1987 after the IRA bombing of the Remembrance Sunday ceremony in Enniskillen. There is now full engagement from the Dublin government and even Sinn Féin plays a role in war commemoration in Northern Ireland.[85] Queen Elizabeth II’s visit to Dublin in May 2011 was an especially important moment of reconciliation. How far there is genuine cross-community engagement with the war during the Decade of Centenaries remains to be seen, which means that part of the story of Ireland’s First World War is yet to be told.

Richard Grayson, Goldsmiths, University of London

Section Editor: Edward Madigan

Notes

- ↑ Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht: http://www.decadeofcentenaries.com/; Dublin City Council: http://www.dublincity.ie/RecreationandCulture/DecadeofCommemorations/DecadeofCommemorations/Pages/DecadeofCommemorations.aspx; Community Relations Council: http://www.community-relations.org.uk/programmes/marking-anniversaries/; and British-Irish Parliamentary Assembly: http://www.britishirish.org/assets/BIPA-Commemorations-Report-FINAL.pdf (all retrieved: 28 April 2014).

- ↑ Jeffery, Keith: Ireland’s Great War, Cambridge 2000, pp. 144-156.

- ↑ IrelandWW1: http://http://www.irelandww1.org/reading/ (retrieved: 18 September 2014).

- ↑ Callan, Patrick: Recruiting for the British Army in Ireland during the First World War, in: Irish Sword XVII, 66 (1987), pp. 42-56; Fitzpatrick, David: The logic of collective sacrifice. Ireland and the British army, 1914-1918, in: Historical Journal 38/4 (1995), pp. 1017-30; Casey, Patrick J.: Irish Casualties in the First World War, in: Irish Sword 20/81 (1997), pp. 193-206; McConnel, James: “Recruiting Sergeants for John Bull”? Irish Nationalist MPs and Enlistment during the Early Months of the Great War, in: War in History, 14/4 (2007), pp. 408-28; Pennell, Catriona: A Kingdom United. Popular Responses to the Outbreak of the First World War in Britain and Ireland, London 2012.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, David: Politics and Irish Life 1913-1921. Provincial Experience of War and Revolution, Dublin 1977.

- ↑ For example, Grayson, Richard S.: Belfast Boys. How Unionists and Nationalists Fought and Died Together in the First World War, London 2009; Cousins, Colin: Armagh and the Great War, Stroud 2011; Yeates, Pádraig: A City in Wartime. Dublin 1914-18, Dublin 2011. There are also many very thorough local books of honour, examples being: Belfast Book of Honour Committee, Journey of Remembering. Belfast Book of Honour, Belfast 2009; and White, Gerry / O’Shea, Brendan (eds.): A Great Sacrifice. Cork Servicemen who died in the Great War, Cork 2010.

- ↑ On the 10th: Orr, Philip: Field of Bones. An Irish Division at Gallipoli, Belfast 2006; on the 16th: Denman, Terence: Ireland’s Unknown Soldiers. The 16th (Irish) Division in the Great War, Dublin 1992; on the 36th: Falls, Cyril: The History of the 36th (Ulster) Division. London 1922; and Orr, Philip: The Road to the Somme. Men of the Ulster Division Tell Their Story, Belfast 1987.

- ↑ Canning, W.J.: A Wheen of Medals. The History of the 9th (Service) Bn. The Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers (The Tyrones) in World War One, Antrim 2006; Taylor, James W.: The 1st Royal Irish Rifles in the Great War, Dublin 2002; Taylor, James W.: The 2nd Royal Irish Rifles in the Great War, Dublin 2005.

- ↑ Gregory, Adrian/Pašeta, Senia (eds.): Ireland and the Great War. ‘A War to Unite Us All’?, Manchester 2002; Bowman, Timothy: Irish Regiments in the Great. Discipline and Morale. Manchester 2003; McGaughey, Jane G.V.: Ulster's Men. Protestant Unionist Masculinities and Militarization in the north of Ireland 1912-1923, Montreal 2012.

- ↑ Hopkinson, Michael: Green against Green. The Irish Civil War, Dublin 1988; Foy, Michael/Barton, Brian: The Easter Rising, Stroud 1999; Coleman, Marie: County Longford and the Irish Revolution 1910-1923, Dublin 2002; Hopkinson, Michael: The Irish War of Independence, Dublin 2002; Hart, Peter: The IRA at War 1916-1923, Oxford 2003; Townshend, Charles: Easter 1916. The Irish Rebellion, London 2005; McGarry, Fearghal: The Rising. Ireland, Easter 1916, Oxford 2010; Townshend, Charles: The Republic. The Fight for Irish Independence, 1918-1923, London 2013.

- ↑ Denman, Terence: A Lonely Grave. The Life and Death of William Redmond, Dublin 1995; Hepburn, A.C.: Catholic Belfast and Nationalist Ireland in the Era of Joe Devlin, Oxford 2008; Reid, Colin: The Lost Ireland of Stephen Gwynn. Irish Constitutional Nationalism and Cultural Politics, 1864-1950, Manchester 2011; Meleady, Dermot: John Redmond. The National Leader, Dublin 2014.

- ↑ Jane Leonard carried out early work in a number of short pieces including: The Twinge of Memory. Armistice Day and Remembrance Sunday in Dublin since 1919, in: English, Richard / Walker, Graham (eds.): Unionism in Modern Ireland. New Perspectives on Politics and Culture, London 1996, pp. 99-114. Important recent work includes: Dolan, Anne: Commemorating the Irish Civil War. History and Memory, Cambridge 2006; Johnson, Nuala C.: Ireland, the Great War and the Geography of Remembrance, Cambridge 2007; Switzer, Catherine: Unionists and Great War Commemoration in the North of Ireland 1914-39. People, Places and Politics, Dublin 2007; Higgins, Roisín: Transforming 1916. Meaning, Memory and the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Easter Rising, Cork 2012; Myers, Jason: The Great War and Memory in Irish Culture 1918-2010, Bethesda 2012; Horne, John/Madigan, Edward (eds.): Towards Commemoration. Ireland in War and Revolution 1912-1923, Dublin 2013.

- ↑ Johnstone, Tom: Orange, Green and Khaki. The Story of the Irish Regiments in the Great War, 1914-18, Dublin 1992; Bartlett, Thomas / Jeffery, Keith (eds.): A Military History of Ireland, Cambridge 1996; Dungan, Myles: Irish Voices from the Great War, Dublin 1995; and They Shall Grow Not Old. Irish Soldiers and the Great War, Dublin 1997; Hennessey, Thomas: Dividing Ireland. World War I and Partition, London 1998; Horne, John (ed.): Our War. Ireland and the Great War, Dublin 2008.

- ↑ Jackson, Alvin: Home Rule. An Irish History 1800-2000, Oxford 2003. See also English, Richard: Irish Freedom. The History of Nationalism in Ireland, London 2006, pp. 207-12.

- ↑ 101 of Ireland’s seats were geographic while two were for Dublin University. Craig, F.W.S.: British Parliamentary Election Results, 1885-1918. London 1974, pp. 580-1, 588. An 86th Irish nationalist was elected in Liverpool. Craig, F.W.S: Minor Parties at British Parliamentary Elections, 1885-1974, London 1975, p. 47.

- ↑ Strictly speaking, men signed the Covenant and women signed a Declaration supporting the men. For texts see: Public Record Office of Northern Ireland: http://www.proni.gov.uk/index/search_the_archives/ulster_covenant.htm (retrieved: 29 April 2014).

- ↑ Bowman, Timothy: Carson’s Army. The Ulster Volunteer Force, 1910-22, Manchester 2007.

- ↑ Jackson, Home Rule 2003, pp. 106-143; Grayson, Belfast 2009, pp. 2-7.

- ↑ Most work states that three were killed in the incident. See, Yeates, City in Wartime 2011, pp. 5-6; Curtis Jr., L.P.: Ireland in 1914, in: Vaughan, W.E. (ed.): A New History of Ireland. VI, Ireland under the Union, II, 1870-1921, Oxford 1996, pp. 145-188 [p. 179 and 184]. However, more recent work states four because it includes a civilian who died of wounds two months later. See, Pennell, Kingdom 2012, p. 23 and http://www.merrionstreet.ie/index.php/2014/07/minister-humphreys-to-attend-events-commemorating-the-howth-gun-running-and-bachelors-walk-massacre/ (retrieved: 11 September 2014).

- ↑ Hansard HC Deb 03 August 1914 vol 65 col 1824.

- ↑ Lewis, Geoffrey: Carson. The Man Who Divided Ireland. London 2005, pp. 167-70.

- ↑ HC Deb 15 September 1914 vol. 66 col. 911; see also: Meleady, Redmond 2013, pp. 304-307.

- ↑ Grayson, Belfast 2009, pp. 13-14; Meleady, Redmond 2013, pp. 309-310.

- ↑ Pennell, Kingdom 2012, pp. 171-172.

- ↑ Bowman, Timothy / Connelly, Mark: The Edwardian Army. Recruiting, Training and Deploying the British Army, 1902-1914, Oxford 2014, pp. 50-51.

- ↑ Doherty, Richard / Truesdale, David: Irish Winners of the Victoria Cross, Dublin 2000, p. 102.

- ↑ Harris, Henry: The Irish Regiments in the First World War, Cork 1968, pp. 216-217.

- ↑ An invaluable online listing of the structure of regiments can be found on “The Long, Long Trail” website at: http://www.1914-1918.net/regiments.htm (retrieved: 12 May 2014).

- ↑ Johnstone, Orange 1992, pp. 17-63 provides detailed accounts of Irish battalions’ involvement.

- ↑ Orr, Field 2006; Cooper, Bryan: The Tenth (Irish) Division in Gallipoli, London 1918.

- ↑ Johnstone, Orange 1992, p. 152.

- ↑ Ibid, pp. 257-268, 318-337 and 400-410; Stanley, Jeremy: Ireland’s Forgotten 10th. A Brief History of the 10th (Irish) Division 1914-1918, Turkey, Macedonia and Palestine, Ballycastle 2003, pp. 78-92.

- ↑ Falls, 36th 1922, p. 8.

- ↑ Denman, Redmond 1995, pp. 117-121

- ↑ Grayson, Belfast 2009, p. 129.

- ↑ Perrett, Bryan / Lord, Anthony: The Czar’s British Squadron, London 1981, p. 43.

- ↑ Grayson, Belfast 2009, pp. 39, 40, 119, 144, 149.

- ↑ Doherty/Truesdale, Irish 2000, pp. 137-138. The connections are tenuous because Mannock appears to have been born in Brighton, only one of his parents was Irish, and he lived his life in England. See: Gunby, David: Mannock, Edward (1887–1918), in: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004; online edn, May 2008 [http://0-www.oxforddnb.com.catalogue.ulrls.lon.ac.uk/view/article/61823 (retrieved: 10 September 2014).

- ↑ A search of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission database (www.cwgc.org (retrieved: 13 May 2014)) for the term “Dublin” in the “additional information” field which shows next of kin details, reveals twelve men on the Indefatigable, seven on the Queen Mary, and six on the Defence.

- ↑ Molony, Senan: Lusitania. An Irish Tragedy, Dublin 2004. See also, Nolan, Liam / Nolan, John E.: Secret Victory. Ireland and the War at Sea, 1914-1918, Dublin 2009.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, Logic 1995, pp. 1017-1030.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 1030.

- ↑ See, Jeffery, Ireland’s 2000, pp. 18-20 for a review of this debate.

- ↑ Bowman, Irish 2003; Denman, Terence: The Catholic Irish soldier in the First World War. The “racial environment”, in: Irish Historical Studies, 27 (1991), pp, 352-65; Denman, Terence, The 16th (Irish) Division on 21 March 1918. Fight or Flight?, in: Irish Sword 17 (1990), pp. 273-287.

- ↑ Jeffery, Ireland’s 2000, pp. 33, 35, 150.

- ↑ Over 49,000 are listed in Ireland’s Memorial Records, but this figure is widely held to be inaccurate since it includes all those who served in an Irish regiment, greatly increasing the numbers while simultaneously excluding those who served outside specifically Irish units.

- ↑ Jeffery, Ireland’s 2000, pp. 6-7.

- ↑ Reilly, Eileen: Women and voluntary war work, in: Gregory / Pašeta (eds.): War 2002, pp. 49-72. For a detailed account of Irish nationalist women’s contribution to, and experience of, the First World War see: Pašeta, Senia: Irish Nationalist Women, 1900 – 1918, Cambridge 2013.

- ↑ Reilly, Women 2002, pp. 66-67.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 49.

- ↑ Jeffery, Ireland’s 2000, p. 32; McEwen, Yvonne: “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary”. British and Irish Nurses in the Great War, Dunfermline 2006.

- ↑ Madigan, Edward, Introduction in: Horne, John / Madigan, Edward (eds.): Towards Commemoration. Ireland in War and Revolution 1912-1923, Dublin 2013, p. 7.

- ↑ Reilly, Women 2000, pp. 58-59.

- ↑ Jeffery, Ireland’s 2000, pp. 29, 32. On women in the workforce pre-war, see: Curtis, L.P.: Ireland in 1914, p. 154.

- ↑ Reilly, Women, 2002, pp. 59-62.

- ↑ Grayson, Belfast 2009, p. 22; Reilly, Women 2002, pp. 63-66.

- ↑ Jeffery, Ireland’s 2000, pp. 30-33; Moriarty, Theresa: Work, warfare and wages. Industrial controls and Irish trade unionism in the First World War, in: Gregory/Pašeta (eds.), War 2002, pp. 73-93; Gribbon, H.D.: Economic and Social History 1850-1921, in: Vaughan (ed.): New 1996, pp. 260-356 [pp. 342-351]; McDowell, R.B.: Administration and the Public Services 1870-1921, in: Vaughan (ed.), New 1996, pp. 571-605.

- ↑ Jackson, Home Rule 2003, p. 149.

- ↑ Wiel, Jérôme aan de: The Catholic Church in Ireland, 1914-1918. War and Politics, Dublin 2003, pp. 1-41.

- ↑ Yeats, W.B.: Easter 1916, in: Dawe, Gerald (ed.): Earth Voices Whispering. An Anthology of Irish War Poetry, Belfast 2008, pp. 9-11.

- ↑ Jackson, Home Rule 2003, pp. 151-2; English, Irish 2006, pp. 260-261.

- ↑ For detailed accounts see, Foy/Barton, Easter 2004; Townshend, Easter 2005; McGarry, Rising 2010.

- ↑ National Library of Ireland: http://www.nli.ie/1916/pdf/1.intro.pdf (retrieved: 2 June 2014).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ McGarry, Rising 2010, pp. 96, 99-100.

- ↑ Jeffery, Ireland’s 2000, pp. 45-47.

- ↑ Department of the Taoiseach: http://www.taoiseach.gov.ie/eng/Historical_Information/1916_Commemorations/The_Executed_Leaders_of_the_1916_Rising.html (retrieved 2 June 2014). The figure of sixteen executions is often given, including Roger Casement (1861-1916) hanged in London on 3 August for collaboration with Germany.

- ↑ Jackson, Home Rule 2003, pp. 158-168.

- ↑ Craig, British 1974, pp. 299-301.

- ↑ Jackson, Home Rule 2003, p. 186.

- ↑ Jeffery, Ireland’s 2000, pp. 6-7.

- ↑ Ferriter, Diarmaid: Judging Dev. A Reassessment of the Life and Legacy of Éamon de Valera, Dublin 2007.

- ↑ Hart, IRA 2003.

- ↑ Barry, Tom: Guerilla Days in Ireland, Dublin 1949.

- ↑ Hopkinson, Independence 2002, p. 40.

- ↑ Townshend, Republic 2013, pp. 285-286.

- ↑ O’Halpin, Eunan: Counting Terror, in: Fitzpatrick, David (ed.): Terror in Ireland, 1916-1923, Dublin 2012, pp. 152-153.

- ↑ Hart, Peter: Mick. The Real Michael Collins, London 2005.

- ↑ Hopkinson, Green 1988, pp. 115-126.

- ↑ Ibid¸ p. 273.

- ↑ See the discussion in Leonard, Twinge 1996.

- ↑ Leonard, Jane: Getting them at last. The IRA and ex-servicemen, in: Fitzpatrick, David (ed.): Revolution? Ireland 1917-1923, Dublin 1990, pp. 118-29.

- ↑ Taylor, Paul D.: Heroes or traitors. Experiences of returning Irish soldiers from World War I, unpublished Oxford D.Phil. Thesis 2012.

- ↑ See note 12.

- ↑ Grayson, Belfast 2009, pp. 167-184; Grayson, Richard S.: The Place of the First World War in Contemporary Irish Republicanism in Northern Ireland, in: Irish Political Studies 25/3 (2010), pp. 325-345.

Selected Bibliography

- Fitzpatrick, David: Politics and Irish life 1913-1921: provincial experience of war and revolution, Dublin 1977: Gill and Macmillan.

- Bowman, Timothy: The Irish regiments in the Great War: discipline and morale, Manchester 2004: Manchester University Press.

- Orr, Philip: Field of bones: an Irish division at Gallipoli, Dublin, Ireland 2006: Lilliput Press.

- Pennell, Catriona: A kingdom United: popular responses to the outbreak of the First World War in Britain and Ireland, Oxford 2012.

- Hopkinson, Michael: The Irish War of Independence, Montreal; Ithaca 2002: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- McGarry, Fearghal: The rising. Ireland: Easter 1916, Oxford; New York 2010: Oxford University Press.

- Bowman, Timothy: Carson's Army: the Ulster Volunteer Force, 1910-22, Manchester; New York 2007: Manchester University Press.

- Foy, Michael / Barton, Brian: The Easter rising, Stroud 1999: Sutton.

- Horne, John / Royal Irish Academy: Our war: Ireland and the Great War, Dublin 2008: Royal Irish Academy.

- Horne, John / Madigan, Edward (eds.): Towards commemoration: Ireland in war and revolution, 1912-1923, Dublin 2013: Royal Irish Academy.

- Grayson, Richard S.: Belfast Boys: how Unionists and Nationalists fought and died together in the First World War, London; New York 2009: Continuum.

- Fitzpatrick, David: Terror in Ireland: 1916-1923, Dublin 2012: Lilliput Press.

- Orr, Philip: The road to the Somme: men of the Ulster Division tell their story, Belfast; Wolfeboro 1987: Blackstaff Press.

- Jackson, Alvin: Home rule: an Irish history, 1800-2000, New York 2003: Oxford University Press.

- Hopkinson, Michael: Green against green: the Irish Civil War, New York 1988: St. Martin's Press.

- Johnson, Nuala Christina: Ireland, the Great War and the geography of remembrance, Cambridge 2007: Cambridge University Press.

- Townshend, Charles: Easter 1916: the Irish rebellion, London 2006: Penguin.

- Jeffery, Keith: Ireland and the Great War, Cambridge; New York 2000: Cambridge University Press.

- Fitzpatrick, David: The logic of collective sacrifice: Ireland and the British Army, 1914-1918, in: The Historical Journal 38/4, 1995, pp. 1017-1030.

- Townshend, Charles: The Republic: the fight for Irish independence, 1918-1923, London 2013: Allen Lane.

- Gregory, Adrian / Pašeta, Senia: Ireland and the Great War: a war to unite us all?, Manchester; New York 2002: Manchester University Press.

- Yeates, Pádraig: A city in wartime: Dublin 1914-18, Dublin 2011: Gill & MacMillan.

- Johnstone, Tom: Orange, green and khaki: the story of the Irish regiments in the Great War, 1914-18, Dublin 1992: Gill and MacMillan.

- Denman, Terence: Ireland's unknown soldiers: the 16th (Irish) Division in the Great War, 1914-1918, Dublin, Ireland 1992: Academic Press.