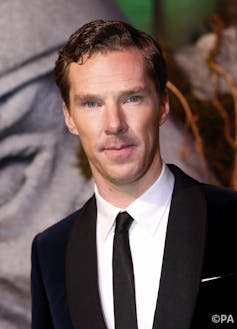

At first glance, Benedict Cumberbatch’s recent faux pas – using the word “coloured” to refer to racially minoritised groups – may appear to have absolutely nothing to do with the world of UK higher education. While some lambasted him, my own view was that his slip-up spoke to a wider issue: the lack of open debate about race in the UK. And if any sector ought to be leading the way in these debates, it is the education system and, in particular, our universities.

Yet a damning new report by the leading race equality think-tank Runnymede Trust, comprising a series of short essays, has set out the continued failings of the sector not just for racially minoritised students but also for faculty members of colour. The issues, as described by Durham’s Vikki Boliver in The Conversation are wearily familiar.

Black and minority ethnic students are less likely to be offered a place at university, even when they hold the same A Level grades. They are less likely to attend the elite Russell Group of universities and, if they do, often feel marginalised when they get there. Among faculty members, black and minority ethnic academics are under-represented at senior levels and, at Russell Group universities generally. They too report being undermined and marginalised.

Race left out of diversity debates

These issues are not new. At the start of the millennium there was a hesitant, inconsistent whimper of activity around race at universities; today the picture is very different. Attention is on “diversity” and one need not scratch very far below the surface to detect that in reality, this tends to mean gender.

There are several reasons for this. The Athena Swan award, which recognises departments that help women working in science, technology and mathematics, comes with financial rewards. Within a sector that is becoming increasingly marketised this is clearly attractive. Gender is also a la mode in policy debates – there is (rightly) a focus on increasing the number women in boardrooms, for example.

Race is a more difficult, controversial and deeply uncomfortable subject, which apparently was resolved in 2009, ten years after the publication of the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry report, when several leading public figures announced the “end of institutional racism”.

Today, government focus is on immigration and terrorism and universities are being encouraged to follow this same policy agenda. Race, if mentioned at all in universities, is often shut down as a discussion point. Or, as Sarah Ahmed from Goldsmiths argues in her essay for the report, relegated to “smiling brown faces” on the front of prospectuses.

Laying blame elsewhere

The wider context is not the only reason for the lack of genuine engagement and change. Universities tend to view and position themselves as highly liberal spaces and in this context the cause of the “race problem” is understood to simply lie elsewhere. The problem apparently lies with the fact that racially minoritised students lack the right grades or mix of subjects, or that academic staff from those backgrounds lack the confidence to apply for that post or go for promotion.

Of course these points are important, but what about the countless occasions when the grades are right, or confidence is not an issue? The introduction of mentoring schemes and voluntary unconscious bias training is part of what I describe as “racial gesture politics”: they appear to offer serious engagement with the issue of race inequality but in reality do very little unless embedded in wider policy change and made compulsory. Isolated, one-off activities are not sufficient to bring about change.

Understanding the link between policy and practice is absolutely crucial. I teach an undergraduate course called “Education Policy and Social Justice” during which students explore the differences between what a policy might state and its actual interpretation and outcome. How policies are interpreted and implemented is central to affecting change on race in our universities. Individual academics, committees and board members are responsible for implementing policy and if they lack a broader understanding of race equality, then little will change.

Senior white men must speak out

One of the sessions on that same undergraduate course focuses on the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry. Commenting on the publication of the Inquiry report in 1999, then home secretary Jack Straw made a bold and powerful statement in parliament that, in my view, warranted far more attention than it received. He said:

Any long-established, white-dominated organisation is liable to have procedures, practices and a culture that tend to exclude or to disadvantage non-white people.

Our universities – despite rigorous equalities legislation – continue to be led mainly by powerful, white men. If we follow Straw’s reasoning, this would suggest that practices and procedures have not only disadvantaged racially minoritised groups but they have also served to advantage those in positions of power.

The forthcoming race equality charter mark currently being piloted by the Equality Challenge Unit may go some way in encouraging universities to take race more seriously. I for one would also like to see powerful white men in our universities take a lead from another high-profile white man, Benedict Cumberbatch. Despite his faux pas, he dared speak out boldly and publicly about the racial injustices in his own industry.