Animal Behavior

Is It Really Natural for Dogs to Belong to Us?

Scientific stories say yes, but Mariam Motamedi Fraser wonders if this is so.

Posted February 6, 2024 Reviewed by Ray Parker

Key points

- "Dog Politics" questions the common perception of dogs as "unthinking objects" or simply "dumbed-down wolves."

- Dogs, unfortunately, are burdened with an especially well-developed species story.

- At its most reductive, this story implies that dogs would still be wolves if it weren’t for humans.

- The book emphasizes understanding dogs on their terms, considering their unique needs and perspectives.

Globally, dogs are extremely popular companion animals. Their lives and relationships with humans range from being very good when people understand who dogs are and what they want and need from us. Then it is extremely dismal when people don't know or don't care about what dogs, who are living in different sorts of captivity and viewed as unthinking and unfeeling objects, want and need to have rich lives; they're allowed to perform dog-appropriate behaviors and simply express their "dogness" and do what they have evolved to do and how they see their worlds.1 All in all, dogs are not our best friends or unconditional lovers. Neither are they dumb-downed wolves.

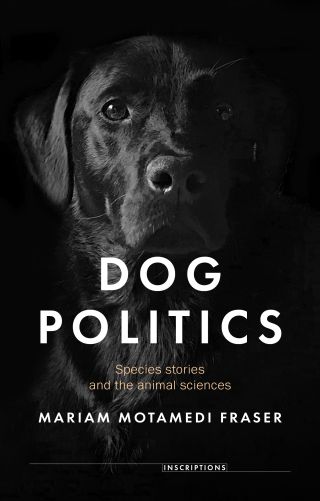

In her interesting and important new book called Dog Politics: Species Stories and the Animal Sciences, Mariam Motamedi Fraser asks if dogs really belong with humans and wants to know what evidence exists to support this idea and what the practical consequences are for dogs.

Here's what she had to say about what dogs think, need, and feel.

Marc Bekoff: Why did you write Dog Politics?

Mariam Motamedi Fraser: The dedication reads: 'To Monk, for Monk.' I wrote it because the more time I spend with Monk (the dog I live with), the more he challenges my preconceptions about what matters to him. I'm also strongly influenced by Susan Close, who runs The Dog Hub in London. The range of Susan's work is very diverse, so being involved in The Dog Hub has given me many different kinds of opportunities to observe the interactions between people and their dogs and also to learn more about the forces that shape the lives of domesticated dogs, in the U.K., as a group. As a consequence, I began to question what is actually 'good' for a dog.

MB: Who do you hope to reach in your interesting and important book?

MMF: Dog Politics could potentially speak to a wide range of audiences. Although this book is aimed primarily at animal studies scholars, some chapters, I hope, will be of interest to people who live or work with dogs. I'm thinking here of chapter one, which is about how we might see and understand dog behavioural 'problems' differently; chapter two, which looks at the evidence for scientific theories of 'how dogs became dogs;' and chapter four, which debates the question as to whether the 'dog-human bond' is a form of labour for dogs.

MB: What are some of the major topics you consider?

MMF: Two key themes in the book are species and the dog-human bond. They're connected.

Dog Politics traces a history of the concept of species. My purpose, though, is not to engage in a debate about whether species really exist or not. I'm more concerned with the real-world implications for animals that follow from using species categories to describe them. That's why I introduce the notion of a 'species story.' It's an invitation to think about how the use of species categories shapes animals' lives in practice.

By species story, I mean a story that draws on evolutionary theories to foreground particular qualities as definitive of all animals in that group. Rooting these qualities in evolutionary time makes them very difficult to contest. Dogs, unfortunately, are burdened with an especially well-developed species story. This is largely on account of the view that dogs' speciation is synonymous with their domestication. At its most reductive, this story implies that if it weren't for humans, dogs would still be wolves. It's a story that puts humans at the heart of what a dog 'is.'

There are many reasons why humans identify dogs with themselves, not all of which are scientific in origin. The historian Éric Baratay, for example, explores the role of early 20th-century literature in creating a vision of 'reciprocal sociality' between dogs and humans. Urbanisation in Europe and North America, which meant the eradication of free-roaming animals, pushed dogs into the home. Nevertheless, scientific accounts of animals remain the most authoritative, which is why it really matters how scientists represent dogs, especially in the public domain. The story that tells that dogs are virtually incomprehensible without humans (which is, in fact, a relatively recent story in science) has serious implications for dogs. It shapes how we expect a 'normal' dog to feel and behave and what treatment of dogs we consider acceptable. For example, the belief that dogs belong 'naturally' to humans can muddy our thinking about the rights and wrongs of using dogs as workers. Dogs' species story also explains why the love of a human for a dog is often conflated with good dog welfare.

I'm not denying how special the relationship between some dogs and some humans can be. It's worth keeping in mind, though, that the ostensibly 'natural' bond is not easily achieved. It takes a lot of effort to produce (e.g., controlled reproduction, socialisation, ongoing training, etc.). And even still, there's plenty of evidence to suggest that many (most?) dogs find it difficult to go along with 'being a dog.' One of the problems with the dog species story is that it means that dogs who have legitimate problems with humans, human social life, and human environments come to be seen as 'problem' dogs ('fearful dogs', 'aggressive dogs'). As a consequence, it's the individual dog who has to change—more medication, more socialisation—rather than the story and the ways of living it authorises.

MB: How does your book differ from others that are concerned with some of the same general topics?

MMF: With regards to dogs, I cover a lot of material that other researchers, across disciplines, address. But I join up the dots slightly differently and, therefore, draw different conclusions. Dog Politics seeks to denaturalise the dog-human bond and interrogate the price dogs pay for it. I think your and Jessica Peirce's book, A Dog's World, also does this, which is why I was grateful to find it and discuss it at length in chapter five.

MB: Are you hopeful that as people learn more about the lives of dogs, they will change their ways and offer their canine companions more freedom to live their lives as dogs?

MMF: Kind of. This book tries to cast a compassionate light on how we understand the behaviours of the dogs with whom we live and work and to reassess the demands we place on them. I don't think dogs should be excluded from public debates about how we live with or alongside animals in a changing world. I don't think they should be excluded on the grounds of some kind of special relationship. It's going to be difficult, though, because the idea of dogs as humans' best friends' is deeply entrenched and thoroughly depoliticised. Understanding and loving dogs differently will require giving up some of our investment in 'the bond' and everything we gain from it.

References

In conversation with animal studies scholar, Dr. Mariam Motamedi Fraser.

1) For further discussion of who dogs are and the hugely variable nature of fog-human relationships see Canine Confidential: Why Dogs Do What They Do; Unleashing Your Dog: A Field Guide to Giving Your Canine Companion the Best Life Possible; A Dog's World: Imagining the Lives of Dogs in a World Without Humans; Dogs Demystified: An A-to-Z Guide to All Things Canine; The Emotional Lives of Animals: A Leading Scientist Explores Animal Joy, Sorrow, and Empathy―and Why They Matter; How to Have a Good and Happy Dog and Be a Better Human' When Dogs Hump, Sniff, and Chew, They're Just Being Dogs; The Best Ways to Build Lasting Connection With a Dog; What Dogs Really Think, Feel, and Need; 3 Keys to a Happier Dog; Canine Anthropology: A Major Shift in Dog-Human Relationships; The So-Called Bad Dog: The Plight of Marginalized Nonhumans; Why "Bad Dogs" Need Love and Help, Not Punishment; The So-Called Bad Dog: The Plight of Marginalized Nonhumans; Is a "Bad Dog" Really a "Bad Dog?"; How Dogs See the World: Some Facts About the Canine Cosmos. Do Pets Really Unconditionally Love and Unwind Us?; Are Dogs Really Our Best Friends?